Gaziantep’s Secret Ingredient

Your night bus from Ankara arrives in far southeastern Anatolia earlier than you expected. It is mid-morning when you climb out into the light of day, surprisingly well rested and, not surprisingly, ravenous. An impromptu committee of bus terminal staff and mini bus drivers convenes on your behalf to help you catch the right city bus downtown. The front desk team at your modest hotel greets you warmly and fetches you a tulip-shaped glass of Turkish tea while they finish cleaning your room and, in a matter of minutes, you’re checked in, freshened up, and out on the streets in search of a late breakfast, less than 70 kilometers from the Syrian border. Welcome to Gaziantep, Turkey’s unofficial culinary capital.

“Little spicy,” your server at the Matanet Lokantasi Beyran Salonu inquires, feeling out your tolerances. You gesture with your fingertips using an upward coaxing motion. “Normal,” he declares with a confirming nod and a grin before hurrying back to the open kitchen. In no time he’s back with a hearty serving of rice and shredded lamb, topped off with a scalding hot, garlicky, peppered lamb broth that has been heated in its battle-scarred serving bowl directly over an open kitchen flame using tongs. Ovals of soft, textured flatbread follow, direct from the oven, too hot to touch, accompanied by plates of sliced white onions, green chilies, sprigs of fresh mint and parsley, and lemon wedges for squeezing.

The broth is bright and smoky, the lamb is moist and the herbs are pungent. From your first spoonful of beyran it is clear there is something special happening on the stovetops of Gaziantep.

Everything you’ve eaten in Turkey has been tasty, but there is an attention to craft and ingredient quality here that shows up in the simplest street fare to special occasion foods. At the Tahmis Kahvesi coffeehouse, established in 1635, their almost four hundred years of experience are evident as you sip the strongest, thickest, most chocolaty Turkish coffee you’ve ever tasted. At Bulvar Döner, you indulge in street side chicken topped with herbs, onions and tomato, served on dürüm, a thin, soft Armenian-influenced flatbread, and rolled up with flair. In your bag you find a stealthy bundle of blisteringly hot pickled yellow chili peppers posing as innocent, mild-mannered pepperoncini. You join the families eating on nearby park benches by streetlamp while every cat for ten kilometers prowls in the bushes, hoping for happy accidents.

Located at a cultural crossroads where Mesopotamia meets the Mediterranean region, Gaziantep was one of the earliest settled regions in Anatolia, and its cuisine has been informed over the centuries by everyone from Neolithic hunter gatherers to Hittite, Assyrian, Persian, Alexandrian, Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman and Islamic foodies. Down a side alley near the copper market, you duck into the Emine Gögüs Culinary Museum where thoughtful displays take you inside the history and traditions of Gaziantep kitchen and let you poke around in the pantry. Along with important economic agricultural crops including wheat, barley, chick peas, grapes and watermelon, the Gaziantep table has a reputation for seducing diners with more unusual ingredients such as wild apricots, crocus bulbs and rose water.

The queen of Gaziantep delicacies, however, is baklava, and the jewels in her culinary crown are pistachios. The fruity, bright green nuts that grow in the groves around Gaziantep are the finest produced worldwide and, for both bakers and sweet tooths, the pursuit of baklava perfection is a local obsession. On the streets of Gaziantep, baklava bakeries outnumber cell phone shops.

“Koçak is the best,” confides the exuberant tourism office representative when you ask her local favorite, and she does not steer you wrong.

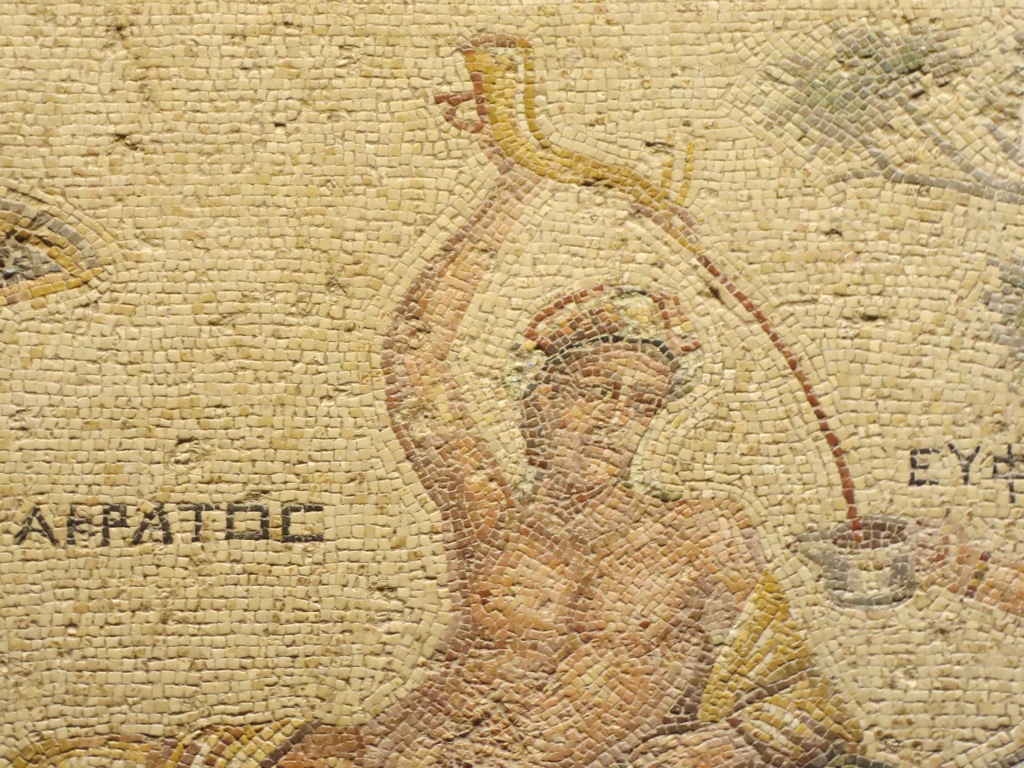

Clearly, Gaziantep is positioning itself to make its mark on the food tourism map. The streets are clearly labeled, the tourism council has multi-page pamphlets in six languages showcasing the regional cuisine, and the 2012 opening of the splendid new Zeugma Mosaic Museum, containing some of the finest surviving Roman era mosaics in the world, ensures more visitors will be passing through.

On a late night walk through the bazaar district, among the mostly shuttered businesses an open baklava shop catches your eye. The portly proprietor, who was not expecting to make another sale, is taking tea on the street corner with his cronies when he sees you and comes jogging halfway down the block to meet you. When you ask for two pieces to go, he nods, nestles the golden cubes out of their tray, picks them up gingerly from one end with little squares of paper, dips the exposed ends into a bowl of freshly minced pistachio, and hands them to you over the counter like the guilty pleasures they are. When you try to hand him money in exchange, he refuses. “My pleasure,” he insists, and sends you off into the Turkish night, smiling.

With a new world class museum and a rich culinary tradition, Gaziantep’s future is bright, but you are leaving knowing that the secret ingredient of the city’s future tourism success will ultimately be the genuine hospitality of its people.

Typing with sticky fingers,

Alison

I am jealous.