The Amazing Örümcek Adam

It is Sunday afternoon and it seems as if every Kurdish and Arab family in a hundred kilometer radius is picnicking and promenading around Urfa’s Gölbasi, a lakeside complex of holy places and green spaces, backdropped by an evocative citadel. Urfa is a pilgrimage site for an exotic array of cultures and religious sects. It is on this site that the profit Abraham is said to have been born and, later, rescued by God from a fiery death at the hands of the vengeful Assyrian King Nimrod. Allah thwarts Nimrod’s murderous plans, turning the fire into water, the pyre kindling into fish and the ashes into a rose garden where Abraham lands unharmed. Today it is believed that anyone stealing a carp from the lake will go blind so, instead, visitors purchase small trays of pelleted fish food to scatter. In this sacred place of plenty, the Pool of Abraham is stuffed to the gills with fattened carp.

The fish aren’t the only ones feasting: fathers and sons share ice cream cones and little princes and princesses throw tantrums at the feet of cotton candy sellers, while working class boys move through the indulgent crowds selling sesame-encrusted simit rings from trays balanced on their heads. Every available patch of shade grass is carpeted with blanket encampments where extended families lounge and feed on chicken wings, stuffed vegetables and sweets. After their picnics, those with extra pocket money don sparkly turbans and robes to pose for novelty photos as ancient royalty. In spite of the crowds, there is a sense of tranquility and contemplation here under the mulberry tree canopy, and the feeling is heighted now as the afternoon call to prayer is sung and carried out over the lake from Urfa’s numerous mosques. Perhaps it is a prayer of gratitude for all of this plenty.

Outside of the Gölbasi, on Urfa’s back streets, the socio-economic challenges facing this rapidly growing city are apparent. We’ve seen more begging in Urfa than anywhere else in our Turkish travels.

As I sit in the shade on a Gölbasi park bench and write notes in my journal, a begging boy about the size of my slight five and a half year old nephew (though I suspect this boy is a year older) approaches me. He is standing here now, calm and composed, pleading his request for aid in a raspy whisper. His voice is deeper than most children’s are, like my own was, like my brother’s was and like my nephew’s is. I look him in the eye, tell him no in Turkish with neither irritation nor malice, but he stays.

Many begging children have approached me in my travels. As an uncomfortable personal policy, my rule is to give nothing. Giving money on the street does not save the child or solve the root problems of poverty and wealth inequity, I tell myself, and an individual gesture can cause a butterfly effect, attracting masses seeking handouts in the moment, and perpetuating begging industries with child laborers in the long run. Not giving money, of course, doesn’t solve the problems at hand either and, the boy reminds me by patiently staying, they are problems I, as a Western woman of privilege and power, I am accountable to help solve. Surrounded by picnicking families and Popsicle wielding children of eastern affluence, he is right to choose me and remain at my side.

Zoom out and we are on the same side of this stand off. We, through our lenses of experience, are both contemplating the same wicked problem and feeling powerless to do anything meaningful. All he knows to do is stay, and all I see to do is write. His voice has quieted. He seems more patient now than he does persistent. His eyes are focused on the tip of my pen. I stop writing and start to draw.

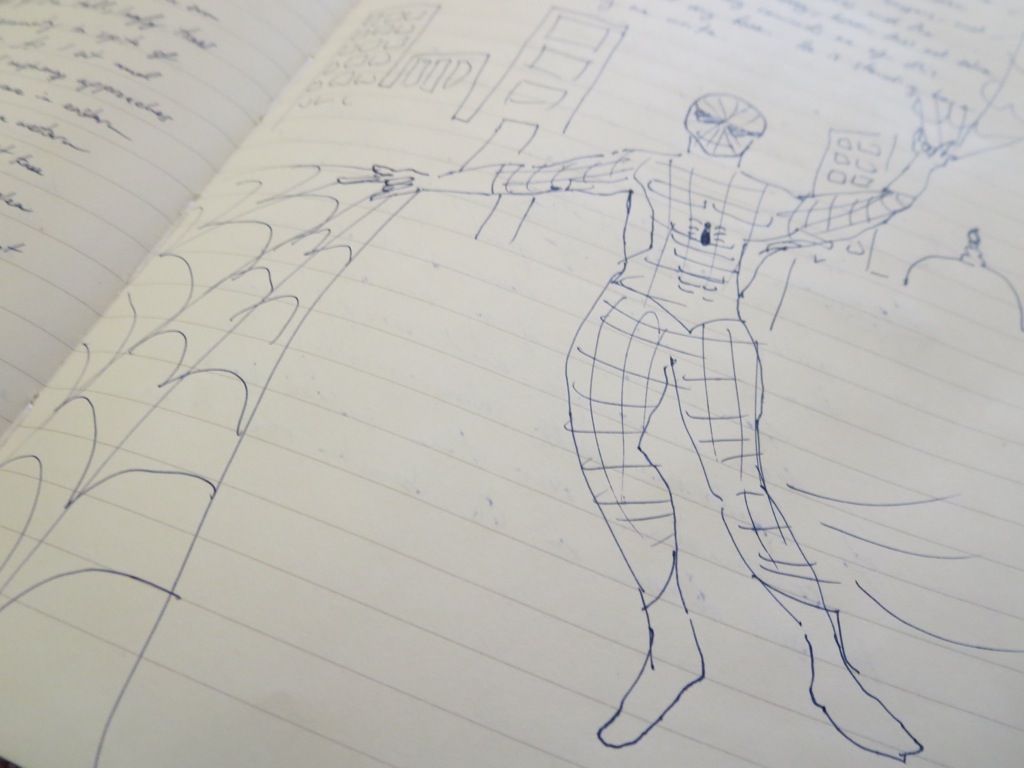

I start with the head and eyes, add a muscular neck and shoulders, and rush to attach an arm. When I get to the fingers – thumb, index and pinky extended, middle and ring retracted flat against an open palm – he knows what I am up to before I spin the first web.

“Örümcek Adam,” he exclaims, naming Spiderman in Turkish.

I finish a quick sketch. My sidekick is riveted. I get out a sheet of clean paper from my bag and scoot over. My sidekick climbs up. This time I sketch more slowly, drawing a complete and careful scene. Spiderman swings along the Gölbasi colonnade over the Pool of Abraham, with the minarets of Urfa’s mosques defining the skyline. I get my sidekick to model Spidey’s web-slinging gesture so I can do a good job on the hands. I draw picnickers in the park. I dig my spare ballpoint out of my purse and, with a little coaxing, get my sidekick to help me stock the lake with carp. I draw people feeding the fish. I draw a watermelon stand with a sign indicating the fruit is free. My sidekick helps me with the seeds. I draw us on the bench. I draw my sidekick with a big slice of watermelon. He stretches out the front of his t-shirt to make sure I get the graphic correct. We give everybody slices of watermelon.

The drawing is finished. Our bench has lost its shade. We put our names on the picture and I give it to him, along with the spare pen when he tries to return it. We get up, make the Spidey sign with our hands and part ways, off to fight injustice to the best of our powers.

Grateful to my nephew for helping me keep my Spidey senses keen,

Alison

Recent Comments