What’s Up, Patna?

Our train shudders to a stop in Patna Junction, the nervous hiss of air breaks reflecting my mood. Have I erred in planning an adventuresome 8-hour layover here?

Patna and its state, Bihar, have a negative image. Even now the guidebooks say things like “…shows few signs today of its former glory.” In his subversive and devastatingly funny novel The White Tiger, Aravind Adiga stings both city and state with his encompassing term “the Great Darkness.”

(Twenty years ago I met a fellow tourist who’d braved Bihar. His bus? Waylaid by rifle-toting bandits. It was a normal Indian bus, not a tourist bus, and after assembling the loot on a blanket and counting it, a heated argument broke out among the dacoits while the passengers were held at gunpoint. In the end, the passengers were given the blanket and all the valuables and sent on their way as if the robbery had never happened: the haul wasn’t enough for the bandits to pay off the police!)

Our train conductor waves his printout, shooing everyone out of the carriage. We have no choice now. Our mission from 3:00-11:00 P.M. (assuming our next train leaves on schedule)? Tourism and a dinner date. Find out what’s up in Patna.

On the almost-invisible-ink map of tourism in Patna, I’ve selected the mighty Golghar as a first stop. At the north end of town, just back from the Ganges flood plain, it’s only 2.5 km from the train station. We’ll secret our bags in the cloakroom and walk.

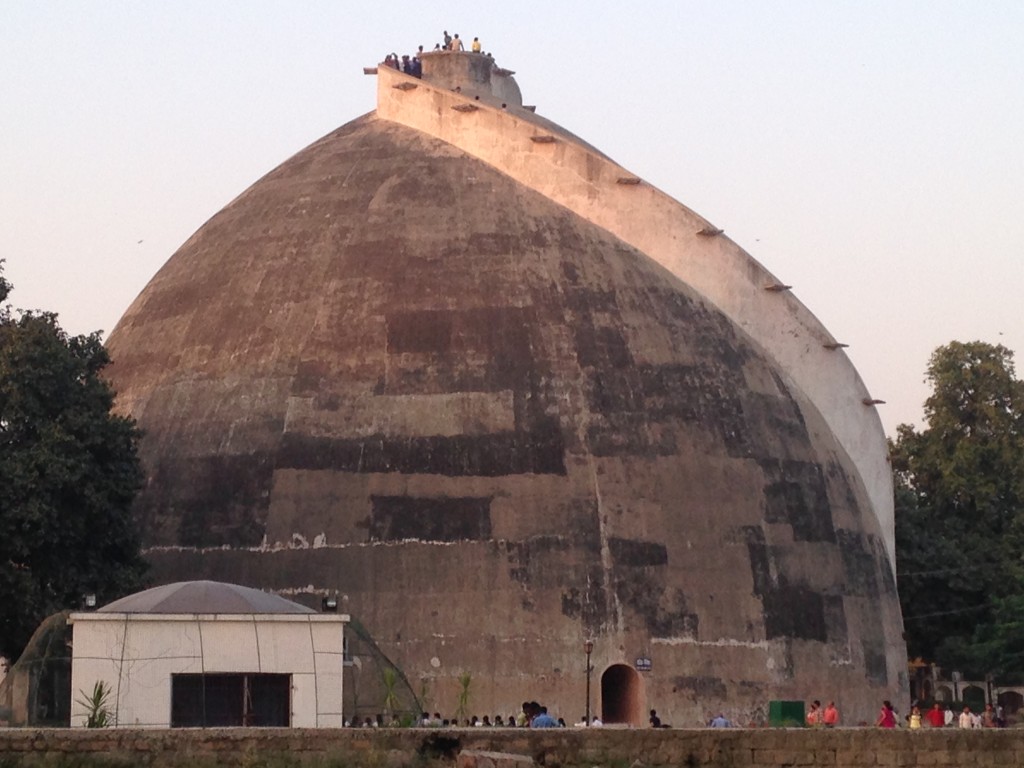

Golghar at sunset. Yes, you have the scale right: those are people standing at the very top. A major restoration project is just beginning. By the time you visit, it may once again be a gleaming white.

What’s up in Patna? Unexpected extra services.

We find it’s not really a cloakroom, but a cloak shed at the east end of the station. It’s dusty and their physical security is not as tight as Old Dehli Station, but the hawk-eyed woman at the counter knows her livelihood depends on our bags (or burlap bundles the size of a sofa or motorcycles packaged for rail shipment) being there when we return. She’s particular about the detail of our passports and makes sure we know we’ll have to show them when return.

The free extra service? In the shadows of the cloak shed’s front door is an electronic freight scale. Its face glows red: “00.0.” I hop on: “88.3.” It appears I’m ten pounds lighter then when I left the U.S.

To weigh myself in most of India, I would have to search street corners for a scale-wallah. That’s someone, probably dismembered or with some other terrible disability, who makes their living charging ten rupees (about $0.16) each time a passerby steps on their age-old bathroom scale.

What’s up in Patna? Expansion. Modernity. Cash.

Five and six story buildings line Fraser Road, our chosen route toward Golghar. They have glassy fronts and sport international brands like “Levi” and “LaCoste.” Why is Patna different now than two decades ago? Low labor costs have made this city a hub for manufacturing. Now a nouveaux riche exists. And they want their air-conditioned malls.

It seems every micro-mall is separated by an ATM. Good. We need cash. Like most Indian ATMs, these are little roadside air-conditioned closets. Sometimes the closet comes with a guard who stands or sits right next to the keyboard while you withdraw your cash, but in Patna, Alison must the play role. She stands resolute guard at the door while I stuff our pockets.

Flush with cash (One guidebook notes “…Patna has a higher crime rate than other Indian cities, and it’s not a good idea to walk around on your own at night.”) we continue our touristy saunter to Golghar.

What’s up in Patna? Tourist traps awash in local citizens.

At Golghar we arrive to pleasant surprise, not skullduggery. The monument itself is intriguing: erected in 1786 by the British Army as a talisman against famine, it looks to the modern eye like a sphere used to store natural gas, but in its time it must have been amazingly modern looking.

An even greater delight is that Patna’s youth flock to this little park. Like us, they pay just two rupees to enter. Then they climb the monument’s giant spiral stair. Teens make eyes at each other under the watchful eye of whistle-toting grounds keepers. Boys of ages 6-20 play a rousing game of amphitheater cricket: there is only one wicket, the bowler doesn’t run, every age can bat, fielders must stay planted on the amphitheater’s bleachers, and hitting it out of the amphitheater is a strictly forbidden because the ball would disappear into the traffic outside Golghar Park.

From atop Golghar one can see the immense flood plain of the Ganges, where even the people of India fear to build. You can’t take a picture at Golgar without getting someone aged 13-20 in the frame. Perhaps some of the young ladies in uniform are from the buildings partially hidden by the trees, which is the Bankipur Girl’s School.

We gawk at the youth of India; they gawk at us. When the park closes at six, we spend half-an-hour posing with people for snaps. The guards and groundskeepers let us linger because we include them in some of the snaps.

What’s up in Patna? Old-style drinking.

As a special treat on our adventuresome date night, I thought we’d have a drink, a beer. Patna is part of the Hindu heartland of India, meaning straight-laced about alcohol, but with nouveaux riche in the town and Australians writing the guidebook, we should be able to find something.

Where we go is Anarkali. If you’ve ever been to a shabby Italian restaurant on the eastern seaboard of the U.S., where the bartender has been wearing one velvet smoking jacket for 30 years and there are always the same two guys at the bar who probably handle cash for the mob, then you know what this Indian joint feels like: dim, red, moth-eaten. Near the door is an aquarium overfilled with fish who’ve been exposed to growth hormone or industrial waste. They’re huge and eerily slow and have an unsettling, alien creepiness to their eyes.

The waiters give us the same creepy look as the fish. Apparently people who drink in India are supposed to drink later than 7:30 P.M. There are three waiters for ten tables. All tables are empty when we enter, so two waiters may stare with carp-like interest while the other tries his hesitant best to serve tourists.

And we do not make it easy by hauling out an old-fashioned order like “one beer each,” or “a whole bottle of Everyday Gold Prestige Whisky, please.”

No, we are bizarre, unpredictable, very thirsty (the walk and Golghar were hot) foreigners who can’t get too tipsy. After all, there’s a train to catch. There may be threats to avoid on the way to the station. No, we’re not easy:

“Two fresh lime sodas, please. And one large Kingfisher with two glasses.”

Bar snacks—spicy corn flour pressed into small rectangular flakes and differently spiced peanuts—arrive before we can blink our eyes. The beer, as cold as if touched by the North Pole, comes along about five minutes later.

Then the clock ticks. And ticks. A full 20 minutes passes before the fish-eyed waiter sets our fresh lime sodas on the table.

Our best guess? Anarkali was out of limes or out of soda. Or out of both. We know they had glasses, because both the snacks and beer were served in glasses. Some junior scullery-wallah had an adventure, prowling the streets and buying the missing items, whatever they were.

I take this scene as a lesson in Indian mixology: you can have your whiskey, or you can have your beer, but you should not have scotch and soda, and don’t even think of trying something as new world as corrupting your beer with a lime.

What’s up in Patna? Superb cuisine.

Date night: the tastes have arrived, but aren’t yet sampled. The mains are still in the kitchen. The waiters are showing the utmost self control here, helping us take a snap without asking to be in the snap.

For our dinner date I’d picked a spot called Bellpepper Restaurant, and from the moment we entered, we sensed we were in good hands.

The décor was modern and felt cared for. The lighting was romantic and the blonde-and-brunette wood paneling helped warm the ambiance, where so many modern restaurants feel sterile.

The waiters hopped to attention when we came in, and instead of running scared from the rare western tourists in Patna, they asked us about our preferences, gave superb recommendations, helped us take a lovely snap.

They also served—smartly, with aplomb—a splendid meal.

It’s the best meal of our trip so far, frankly. We are living proof that Patna is what the Biharis have been trying to tell the rest of India for years: a city with superb food.

These tasted sweeter and more delicate than red onions I’ve previously sampled. Was it the variety? Cultivation? Preparation? More than one factor?

Let me tantalize you with what was laid on the table to accompany our meal: pickled red onions and what the Indians call ‘mixed pickle.’

The purple onions had lain in vinegar that was just-barely sweet and slightly clove-tinged. Bright. As inviting to the nose as the eye. It’s not often we want to pick up an onion and eat it whole, unaccompanied. These onions were that good, and we did. They begged a giant Gibson, but alas, Bellpepper is a dry restaurant.

As it is impossible to imagine a restaurant in the United States without mustard, so it is impossible to imagine a restaurant in India without having mixed pickle. The problem for both condiments is that they are easy to ignore. “We must have some, so put the cheapest thing we can buy on the table.” For mixed pickle that means we often get a briny, sour, limp-wristed paste with nearly no unique flavor components.

Let there be no doubt: this was the very best pickle we have enjoyed in India. Flamboyant! Powerful! Scrumptious!

Indian pickle is an art unto itself, and has been the crux of entire novels: wondrous, intense, containing intricate complexities. If you have not read Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie, now is a good time to take a break from this blog and digest that masterwork.

The mixed pickle at Bellpepper did the nose of Saleem Sinai most proud. Chunks of lime and mango and okra and other vegetables could be clearly differentiated with the naked eye. Lovingly wrapped in a salty, tart, and sharply peppery sauce, the taste of each vegetable shown through when we ate that vegetable, and a wonder of combinations flashed across our tongue when we began mixing components. The sauce of the pickle was acting like wine would in a French meal, creating fusions of flavor that would not otherwise be possible. The chef had made that pickle by hand, using fermentation, not preserving with acidity alone. His work was nothing short of superb!

The vegetable jalfrezi from Bellpepper. The creamy texture was unusual and the flavor mixture more toward the green side of the spice spectrum, complimenting the exquisite vegetables they used. Dig those peas! Yum!

The mains? Let me say that I chose Bellpepper because I’d read about its murg tikka lababdar. That’s a boneless tandoori chicken basted with garlic, ginger, green chillies, and a pistachio- and cashew-nut paste. I have never had a French cream sauce as good as their puree of pistachios and cashews. Otherworldly!

To that we added platter of vegetable jalfrezi. When we can get it (It’s originally a Pakistani dish, so not surprisingly, many restaurants in India won’t serve it.), it’s one of the dishes we use to compare one subcontinental kitchen to another. Because green chilies are always a part of the recipe, it’s a dish we can talk waiters and chefs into making it as spicy as they would for themselves.

Bellpepper’s base was the creamiest sauce we’ve had in a jalfrezi (typically it’s done with a dry stir-fry technique). Among the tangle of onions, they included a large handful of fresh peas, which, from the looks of markets we’d passed next to the ATM between the malls, were just reaching the peak of their season. Fresh, delicious, and fiery.

What’s up in Patna? A light show.

To live up to its reputation, the capital of Bihar should have lined to road from Bellpepper to the station with cutpurses and cutthroats.

On our walk to the train station we got a special invitation from a local merchant. Time did not allow us to try the wears, alas.

Instead, we had the unusual pleasure of neon. A sweet shop here, a movie theater there, and, seemingly on top of the rail station, a vast temple tipping every edge of its pagoda hat to Bihar’s contribution to Buddhism.

The tubes, their color and sizzle, are the stuff of every evening to the natives of Patna, but to us visitors, the warm glow helps push this city beyond “wrong side of the tracks” and into “surprising splendor.”

Pagoda tops lit with neon near the Patna Junction station. Note the cheery, helpful sign of the Patna police in close proximity. We didn’t need them, but they seem ready to spring into action.

Yours from the land of shattered expectations,

Chris

So, you’ve already answered my question from the other post: Lost 10 pounds so far on the trip, gained it back in one meal!