Piecing Together the Acropolis

I was an eighteen-year-old college student the first time I visited Greece. It was January and I was interning at an American international school in Athens when the US initiated Operation Desert Storm. The school proactively closed for a week in case of local terrorist activity against American targets abroad. A few young instructors borrowed a school van, and we opportunistically spent the first week of the war visiting ancient Greek ruins during the offseason with a handful of international high school students from the boarding program. When we visited Delphi in 1991, there was no guard on duty to keep our careless caravan from climbing directly on the Oracle of Apollo, running races down the length of the ancient athletic stadium or sitting in the stone judges’ chairs.

We weren’t the only ones who saw wartime in the Gulf as an opportunity to take advantage of ancient antiquities while the attention of authorities was focused on current events. In the wake of the first Gulf War, the systematic looting of archaeological sites in Iraq began on a large scale, and escalated at the time of the 2003 coalition invasion when the National Museum of Iraq was professionally raided.

Today, walking through the Ancient Agora in Athens where democracy was born, where Socrates professed, and where classical theater, sculpture and the pursuit of high art was celebrated, I find it impossible not to feel, even in its ruined state, that the place is still inviting us to believe in and pursue societal and intellectual ideals. What remains of the Acropolis on the table rock above, after being ravaged by everything from Persian gunpowder explosions and Venetian cannon balls to vandalizing missionaries, rogue antiquities collectors and acid rain, still powerfully conveys the architects’ vision of aesthetic perfection. The bases, rooflines and columns of the Parthenon, deliberately carved convexly and concavely to correct for the distortions of human eyesight, have been challenging us to see and think in ideals for hundreds of centuries.

These same ancient objects, however, that persist in asking us to consider the world and ourselves in perfect light also continue to bring out the worst in us. Acts of Acropolis-inspired greed, envy, neglect, vandalism and theft are still playing out today. While the sculptures that surrounded the Parthenon were highly refined and perfected in technique, their subject matter was raw and conflicted: mythological battles, mortal combat and, perhaps most prophetically, the rape and carrying off of the Hellenic women by the centaurs.

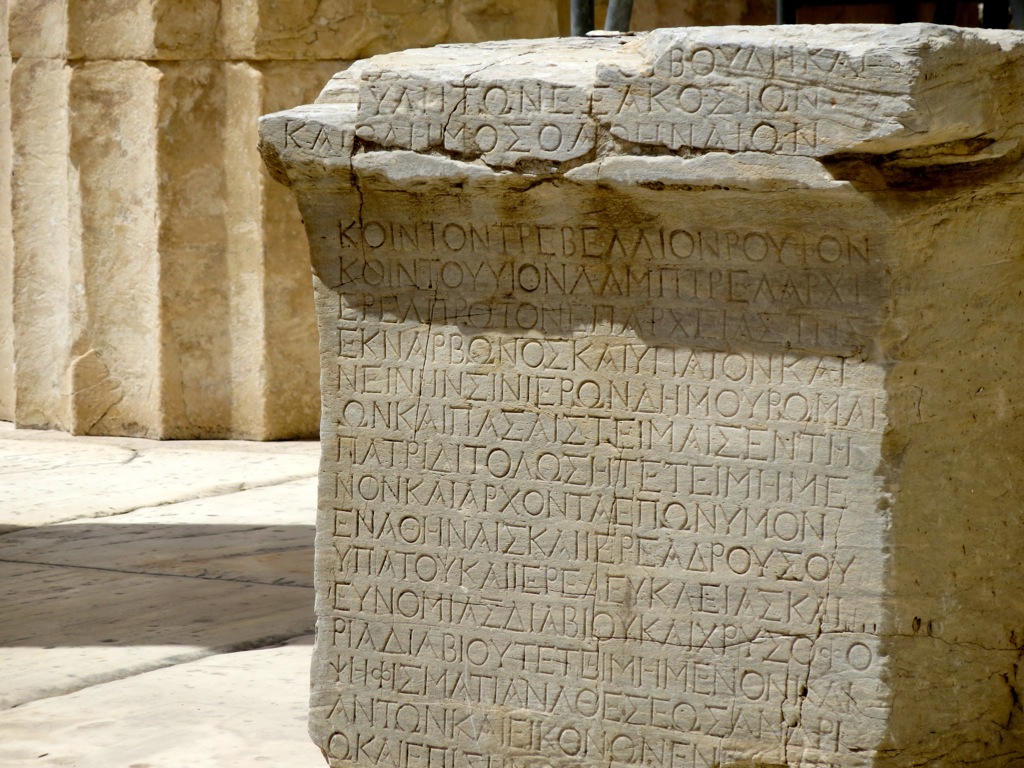

High relief sculpture from ancient Delphi, similar in style to those taken by Lord Elgin from the Parthenon

Between 1801 and 1805, Lord Elgin, British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, seized an opportunity, with the allegedly bribed permission of Ottoman officials, to chisel off, lower down and ship away half of the surviving Acropolis sculptures. The pieces, now known as the Elgin Marbles, were then purchased promptly and at a discount by the British Museum, in whose collection they controversially remain today. The British Museum’s website portrays Lord Elgin as a man “passionate about ancient Greek art,” acting legally and within the best interest of the sculptures. Standing in the stunning, new Acropolis Museum this week, however, in front of the incomplete jigsaw puzzle of sculptural remains, I found myself asking how Elgin’s original removal of, and the British Museum’s continued retention of, the sculptures is any less barbaric than the lustful acts of the mythical centaurs depicted in some of the very reliefs in question. The Greek government has been unsuccessfully petitioning the British Museum for the return and repatriation of the missing Elgin Marbles since the 1980s. Display areas in the new Acropolis museum, built to house the missing works, stand empty, awaiting their return. International pressure for the return of the sculptures to Greece is increasing.

One of the six original sculptures of women holding up the Erechtheion at the Acropolis was carried off by Lord Elgin.

As Chris and I plan our onward travel to Turkey, I feel connected in ways I didn’t twenty years ago to the role my own country’s military action is playing in creating a thriving illegal antiquities market, and to the heightened risk of destruction and theft facing the art of ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Syria and Islam today. I’m leaving Athens with a deepened conviction in the importance of ancient antiquities preservation and repatriation, in general, and a specific belief that the British Museum should return the Acropolis sculptures to Greece. It will take an act of rare power to heighten global awareness about ancient arts and culture preservation, and to unify global action when antiquities representing the best of humankind’s capacity are at risk. Based on the fragments I’ve seen, the remains of the Acropolis, reunited, may contain precisely the rare power of image and gesture needed now to inspire collective action.

Preaching from a Doric pedestal,

Alison

A few references:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Bruce,_7th_Earl_of_Elgin

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/making-a-difference/looting-iraq-16813540/?no-ist

http://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/01/international/worldspecial/01ARTI.html

Read the British Museum’s position on the Elgin Marbles here.

Learn about Greece’s position on the Elgin Marbles here.

I’m inspired. By your words as well as the fact that your hair looks just as great on the other side of the world…

Ug. Thanks, but I’m pretty sure both my words and my hair could use a trim.