The Devil is Dead, Part 6

Finnegan and Anastasia had rented a donkey, loaded it with two paniers, and gone to visit Anastasia’s grandmother, the matriarch of the Demetriades. This was a winding road, uphill for four miles.

Our Naxos picnic will not rely on the sinew of a donkey. We start by climbing aboard one of the island’s buses. To our surprise, it is standing room only: one third filled with tourists headed to the distillery and art colony hamlet of Halki, a third filled with tourists like us trying to see the rugged heart of the island, and a third filled with Naxians visiting family or doing business.

All riders, in seats or standing, sway through a half-dozen switchbacks as we grind uphill.

With such a full bus, we’re surprised when so few debark at Filoti, the largest of the inland villages and one of the highest. The bus grinds on to destinations unknown.

A Greek Orthodox chapel sits atop one of the lesser peaks of Naxos. It seems a tradition to build these tiny churches and then keep them blindingly white.

On foot we wind higher and higher, first on the main road, then on narrower pavement, and finally on a dirt track. We pass a few goats, some shaded under scrub, some grazing on thistles and bunch grass. Their bells clap gently.

The dirt track ends. We climb still higher, the trail reaching a cool spring where the water supports huge, ancient trees. Then we pick our way through stones and around cliffs to the highest slopes of Mt. Zeus.

This uphill climb is at a lovely and complex moment for Alison and I: we are nearing an apex of this trip. The Devil is Dead is of great personal importance to me and we are structuring a good chunk of the journey to embrace the novel, to be on this island, to be climbing this very mountain. That’s the lovely part. That, and to be climbing through sunshine with your pal, all the while anticipating a picnic.

“How do we explain to people about the donkey?”

“He does make us look like an old married couple. We could pass off a child with some story or other, but how do you explain a donkey? We’ll have to pretend that we don’t know him. Sorry, Papapaleologus, we love you, but we can’t let on that we know you. Stop walking between us. You stay three steps behind.”

The donkey was named Papapaleologus, being a lineal descendant of the last Roman Emperors of the east.

We haven’t a donkey.

A dolphin? Yes, we have a dolphin. I suspect he makes us look younger, not like an old married couple.

Yet the complexity of this moment is weirdly wrapped up in the dolphin.

We’re not going to have children. Our journey this year is, in part, a celebration of this truth.

And yet how do we explain the dolphin? How do we explain ourselves to people we meet who assume by our age that we must have children? What is our purpose if we do not embrace that biological imperative?

We know a few things. We have a few answers. And we are still traveling.

We must be something to all the children we meet. We must be a great deal to a few children. Dolphy keeps us thinking about Ian Mock and his sister Arika: to them we must be a great deal.

Hardly a day goes by that I don’t think of a shrimpy little boy—Was he six? Was he seven?—we encountered alone on the streets of Meknes, in Morocco. He wanted to cross the street, that was plain from his hesitant dance between the curb and the roadway, but the street was terribly busy and he was afraid. Big saucer eyes at all the whizzing cars.

We also wanted to cross that road. Our adult eyes saw an opening—when we stepped into the gap I turned and motioned to him to follow in our traffic shadow.

He didn’t stay close, nothing near hand-holding distance, but he walked as we walked. When we three reached the far curb, his meek, high voice gave an audible “Shukran,” before he turned and hurried away. ‘Thanks.’

To all children we must be something.

Finnegan unloaded the paniers that Papapaleologus had carried up the hill; and spread out bread, oil, honey, eggs, coffee, cheese, wine, pickles, sugar, rice, tea, milk, flour, salt, chocolate, and tobacco. Then Finnegan and Anastasia went to a neighbor and bought a kid.

Alison shows off our daily bread. The bread from Velonis bakery in the twisted streets of the old market in Naxos Port was absolutely superb, on par with anything we had in France, Spain, or Italy.

We pause our climb near a cave on the southern side of the mountain. There is a scruffy tree, hardly more than a bush, which was probably here when the Naxians last sent tribute to the Oracle at Delphi. We spread our blanket in its shade. Shade built for two.

Our picnic has these elements in ritual or more significant quantities:

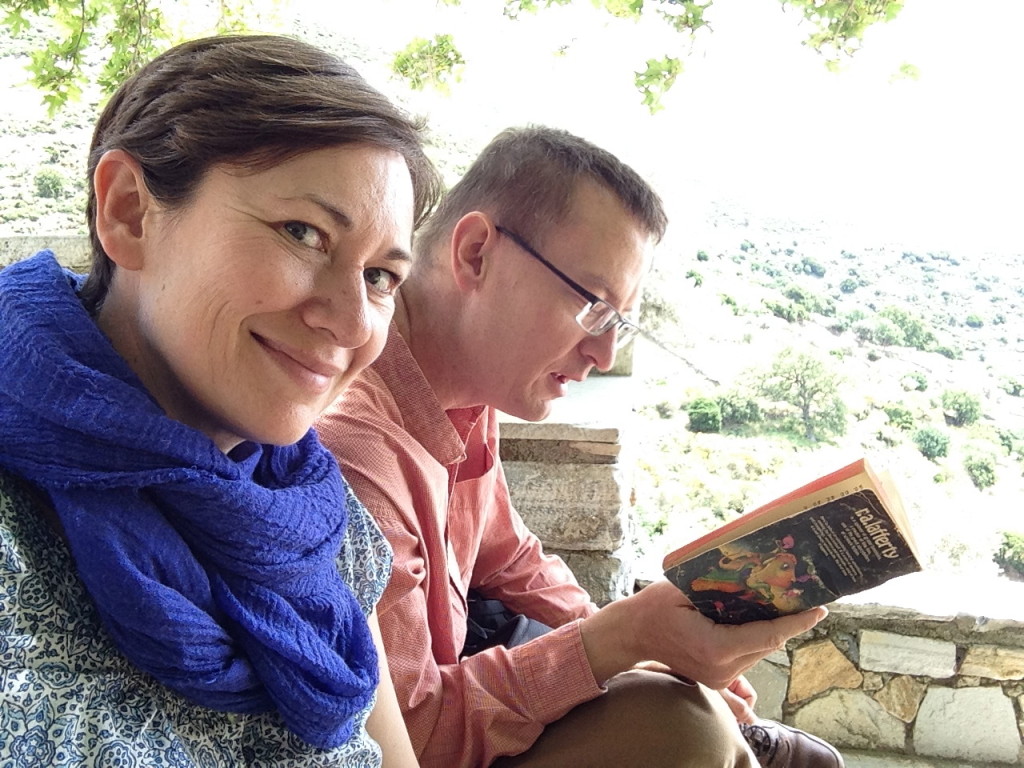

Alison’s improvements and Lafferty’s prescription side by side in the shade. We suspect the cherries were from Naxos: how could fruit in such ideal condition and at the peak of flavor have arrived by boat?

- Bread

- Olive oil

- Eggs

- Coffee

- Cheese

- Wine

- Pickles

- Sugar

- Tea

- Salt

- Chocolate

Alison has improved on Lafferty’s recipe by carrying a ripe Aegean tomato and a half-kilo of perfect cherries in her pack.

The local goats are safe. They live to bleat another day.

They ate and drank outdoors at a little table. Eating and drinking are ordinary things; everybody does them. Yet this was somehow remarkable: to be eating outside of a little farm house on the side of a blue mountain on a Greek Island.

It is deeply remarkable to be eating on the side of a blue mountain on a Greek Island.

I am a man with mysterious business in many small ports.

We sip at our liter and a half of wine. I read the Naxian chapters of The Devil is Dead aloud. We carve the dry, strong cheese of Naxos and eat it with lush tomato slices sprinkled with oil and salt.

We are a couple with time to spend together in shady, out-of-the-way spots all over the planet. It will be complex and perhaps lonely, later.

For now it is sublime.

At an apex,

Chris

Read this in a pause from taking photos at a wedding.

Complex is the right word.

Stay tuned! The Devil ain’t dead yet!